Bio-waste, also known as bio-degradable waste, can be used as fuel to generate electricity and as compost for the agricultural sector. Even so, only 16% of bio-waste is separately collected in the EU, making this valuable resource largely untapped. The majority is incinerated or landfilled, contributing further to carbon and methane emissions. That’s why the European Union has made bio-waste collection mandatory for all member states by the end of 2023. The city of Milan in Italy is leading the way.

How bio-waste can become an issue if not properly managed

Bio-waste makes up almost one-third of household waste. The bulk of it are organic materials such as food and garden waste. When mixed with other waste, such as plastic, it ends up in landfills or incinerators. In landfills, it will eventually decompose and ferment, leading to leachate generation in the soil and methane emissions. If bio-waste is incinerated, it contributes to CO2 emissions. This creates many problems for our environment and, eventually, our climate.

Considering this, instead of burying or burning bio-waste, it would make much more sense to separate it from residual household waste and adopt a process for returning it to the soil. Separately collecting and decomposing bio-waste means recycling organic matter into nutrient-rich fertiliser, for which demand is rapidly increasing.

The European city leading by example: Milan

Even though most countries are still lagging on recycling bio-waste, some regions in Europe are implementing effective food waste collection programs. Milan and a couple of other smaller to medium-sized Italian cities have already adopted ambitious plans in this regard over the last ten years. It can act as an example of excellent local practices when it comes to separating bio-waste.

The city of Milan has the second-largest population of any city in Italy. In 2011, the city’s food waste collection was around 35%. After implementing a comprehensive program for separate food waste collection through AMSA – the Milanese Environmental Services Company – the city is likely the best example for separate waste collection in European big cities. In 2019, 110kg of food waste was collected per person, compared to an average of 18.8kg in the rest of the EU. It is beneficial to Milan’s whole waste collection system, with the city’s overall separate collection rate being 62.6% in 2020.

Implementing the food waste collection for a city of 1.4 million inhabitants, of which about 80% lives in high-rise buildings, was the primary logistical challenge in the strategy. For this reason, a separate collection system was developed for three major categories:

- Commercial activities such as bars and restaurants

Before implementing the comprehensive plan in 2012, Milan already had a food waste collection for commercial activities in place since 1997. For these institutions, the city provides criteria for door-to-door collection, provision of 120-litre bins, and daily collection from Monday to Sunday at night. Food waste from commercial activities corresponds to around 25% of the total food waste collected within the city.

- Households

Households make up the bulk of collected food waste in Milan. To implement a separate collection for this stream across the entire city, it implemented curbside collection from houses, the provision of varying sizes of bins and compostable bin bags, and collection twice a week.

- Open market

The latest progress regarding food waste collection in Milan started in 2017, targeted open markets around the city. In 2019, the system resulted in 2000 tons of food waste to be collected and then composted, by providing markets with compostable bags and holders, plus collecting every day after the market closes.

Economic and environmental benefits of separate bio-waste collection

The separate collection and treatment of 130,000 tons of food waste annually, results in savings of around 8760 tons of CO2 emissions, the equivalent of 4600 flights from Paris to New York. Once food waste is sorted and inspected, it is sent to the Montello treatment plant. The plant, which has not even reached its full potential yet, produces both biogas and compost. The biogas is used for AMSA vehicles running on biogas, such as collection trucks. About 20% of the high-quality compost, nutritious enough for organic food production, is distributed for free to farms and households, while the rest is sold.

In addition, diverting high quantities of food waste from landfills or incineration to be properly recycled instead can reduce a city’s disposal fees. In the Lombardy region, it costs approximately €100 to dispose of 1 ton of residual waste and €70 for treating and composting 1 ton of food waste. This means the region saves about €30 per ton diverted.

Additional benefits of separate collection of bio–waste

Ten years after implementation and continuous improvements, the Milan case has shown great results. Overall, contamination rates are relatively low, meaning simpler and quicker treatment of biowaste. However, problematic products such as plastic bags and nappies remain a challenge, despite the low contamination levels.

In addition, by separately collecting bio-waste, other waste collection streams also benefit. For example, there is less need to collect residual waste since this waste stream was previously primarily composed of food waste, so fewer collections are needed. Also, recyclables like plastic are not contaminated as much by food scraps. This makes them of higher quality, easier to recycle and retain more value when recycled.

Communication is key to good bio-waste policy

The plan’s logistics would have been rendered ineffective without the support and participation of Milan’s citizens. Before the first rollout phase, two pilot programs were run in small areas of the city in 2008 and 2010. Workers were trained to collect food waste, but also educate citizens about the new collection process.

This two-month campaign utilised leaflets, posters, school programs, a free app in ten languages catering to Milan’s diverse residents, a website, face-to-face communications, and online 24/7 customer service. To encourage compliance, financial penalties have also been introduced. A household or business that has too many impurities or contamination within its separate food waste bins, for instance, could be fined.

Achieving even higher separate collection rates as a city

Milan is one of the best examples of food waste collection in the EU. However, one next step the city is considering to achieve even higher collection rates, and make full use of the Montello treatment plant, could be a pay-as-you-throw (PAYT) system. In this scheme, residents are charged for the collection of waste, based on the amount they throw away. This creates a direct economic incentive to recycle more and generate less waste.

Another important step would be to reduce reliance on incineration. Instead, opt for a broader zero waste strategy, crucially including a transitional solution for residual waste that is sustainable and aligns with Europe’s long term vision for a circular economy and a decarbonized society.

An opportunity for European cities

With the deadline quickly approaching for all EU Member States to be collecting bio-waste separately, the story of Milan shows how other cities across Europe can follow in their footsteps, even in challenging circumstances. It shows that with a well-designed plan, a high collection rate can be achieved in a densely populated city. Next to that, it’s clear that by focusing on food waste, the whole waste management system will benefit.

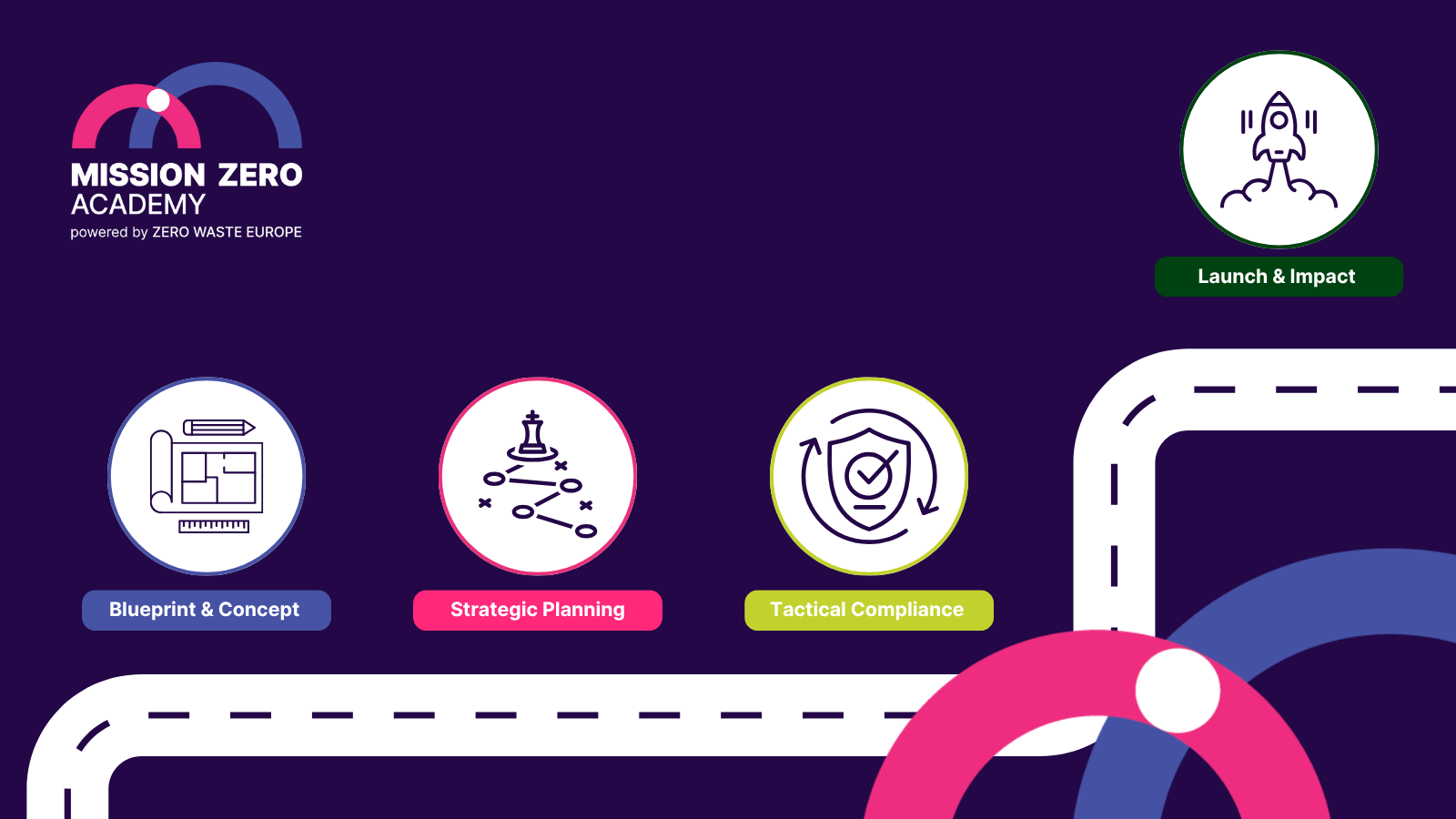

If you would like to know more about the different approaches to bio-waste collection for municipalities, watch our free MiZA webinar. In this webinar, we sit down with Enzo Favoino, Chair of Zero Waste Europe’s Scientific Committee. You’ll learn why bio-waste is a fundamental chunk of a circular economy.