Managing food and organic waste is vital to any city’s zero waste plan. A quarter of the greenhouse gas emissions from food come from losses and waste in supply chains and by consumers. Cities should ideally reduce waste, recover and process organic waste by separating it from dry recyclables like plastic and glass.

From December 2023, separate collection of bio-waste will be mandatory across Europe to help meet EU waste rules’ ambitious recycling and collection targets. However, collection systems and rates still differ substantially among the 28 EU members.

This article outlines some of the best examples for managing organic waste in Europe. We’ll go into best practices for collection, communication, and community involvement.

What is bio-waste?

Biodegradable waste, commonly referred to as bio-waste, is primarily made up of organic materials which can safely be returned to the soils via natural processes. It mainly consists of garden waste, food waste and other organics from households, restaurants, and shops.

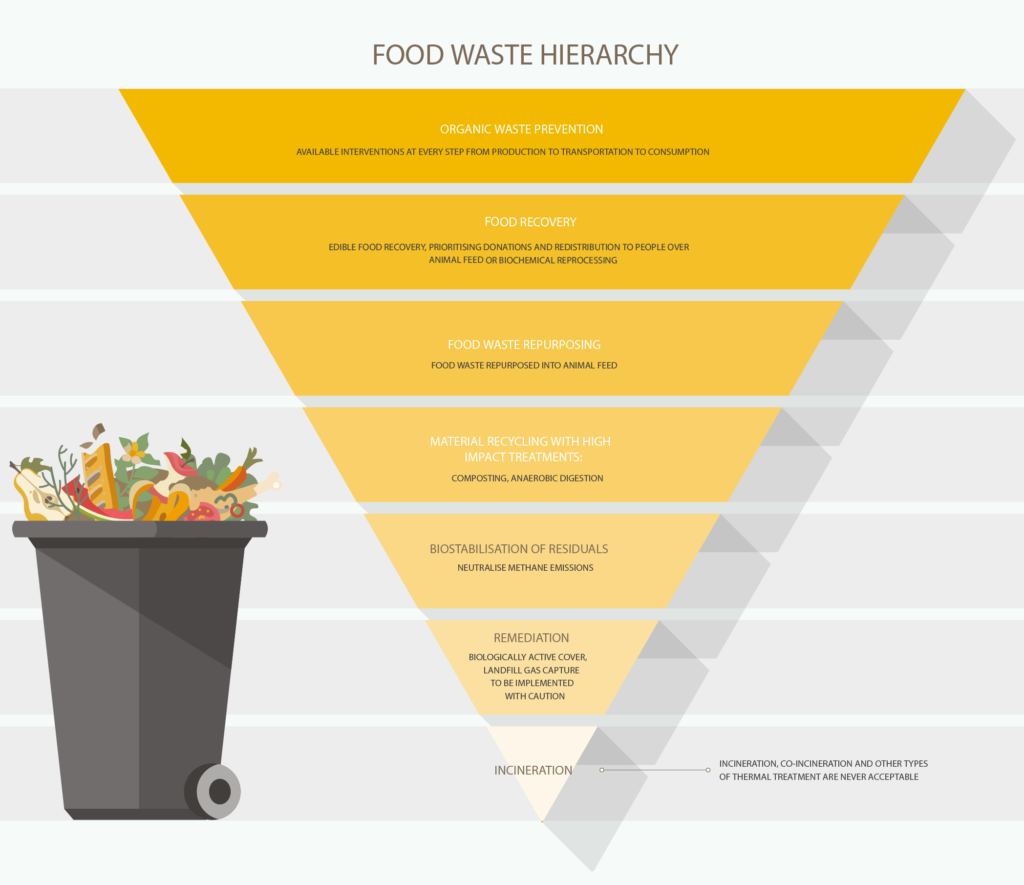

While, according to the waste hierarchy, we should ideally reduce, reuse, or recycle all waste, in practice, this does not always occur. Processing issues, poor planning, or a lack of communication/knowledge are just a few examples that can lead to losses.

Source: “Methane Matters – a comprehensive approach to methane mitigation”, page 16, Changing Markets Foundation, Environmental Investigation Agency and Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives.

How bio-waste impacts efforts towards a circular economy

Nearly one-third of household waste is bio-waste, primarily consisting of food and garden waste. Most often, it is mixed with other residual waste, such as plastic, and can end up in landfills or incinerators. Once dumped in landfills, organic waste attracts microorganisms, activating the decomposition process. The result is the production of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

Additionally, when food waste mixes with residual waste, it may contaminate plastics, paper, and glass. Recycling these materials may then no longer be possible. On the other hand, bio-waste contaminated by plastics may impact the recycling into natural fertiliser. Therefore, residual waste should contain as little bio-waste as possible.

The separate collection of bio-waste is an essential step to achieving this. With high separate collection rates, bio-waste can support a circular economy. Among its potential uses are soil-improving materials and fertilisers.

Increasing bio-waste collection rates at the local level

A crucial step to minimise emissions and contamination is separating bio-waste from other waste streams. There are several strategies to help achieve this. Here are some examples from local and state governments improving bio-waste collection through different approaches.

1. Communication is key: Milan

When it comes to collecting bio-waste in a dense city, Milan is an outstanding example. With 1.4 million residents, it is one of Italy’s most populous cities. Yet, it is a shining example for others around the world.

In 2014, Milan rolled out their residential food waste collection program. Every single household received a 10-litre kitchen bin, compostable bags, and an extensive information packet. As part of the plan’s extensive pilot program, communication proved to be key in the logistics.

Workers were not only trained to collect food waste, but also to educate citizens about the new collection process. The campaign also included leaflets, school programs, a free app and website in multiple languages, face-to-face communication, and 24/7 customer service.

Additionally, there are financial penalties in place to encourage compliance. For instance, a household or business that does not use the provided separate food waste bins receives a fine.

2. Nudge decision-makers with incentives: Catalonia

Catalonia’s landfill tax and refund scheme shows how a public authority can provide a structured approach to collecting bio-waste. This tax scheme charges municipalities for landfilling and incinerating waste, following the “polluter pays” principle.

Financial incentives encouraged municipalities to adopt more efficient bio-waste management practices, such as prevention and separate collection. The tax itself, in turn, facilitates the increase of door-to-door collection systems.

3. Join forces to promote food waste collection: France

Separate collection of bio-waste was a neglected practice for many years in France. Until 2007, a network that brings together municipalities, called Reseau Compost Plus, successfully started bringing visibility to the bio-waste sector.

By joining forces, the network of 28 communities with around 9 million inhabitants introduced food waste collection at the local level. The Reseau Compost Plus provides public information, including recommendations and cost estimates. The network also manages quality assurance for compost and promotes best practices through local events.

4. The proximity principle: Austria

Austria successfully implemented the “proximity principle” in the management of bio-waste. This means that it follows the premise of as much home composting as possible. A brown bin offers a solution wherever home composting is not possible.

Likewise, agricultural bio-waste is decentralized, promoting as much on-farm composting as possible. Austria also introduced a ban on landfilling bio-waste to support their efforts in 2009.

Other best practices for high separate collection rates

There are a few common denominators among countries that achieve high collection rates. Nations that traditionally perform well in separate collection, such as Austria, the Netherlands, and Belgium, typically:

- Use bio-bins, typically wheeled bins for garden and food waste.

- Equip household kitchen caddies for temporary collection/storage in the kitchen.

Meeting the 2024 deadline for separate collection

Organic waste cannot be recycled and captured in its entirety. However, taking everything into account, an 85% capture rate is realistic and essential if the EU wants to fulfil its recycling targets.

Governments and municipalities must scale up their efforts to meet the 2024 deadline for mandatory separate collection. The above examples show how European cities can achieve this, even in challenging circumstances.

This article is based on the report ‘Bio-waste generation in the EU: Current capture levels and future potential’ by Zero Waste Europe.